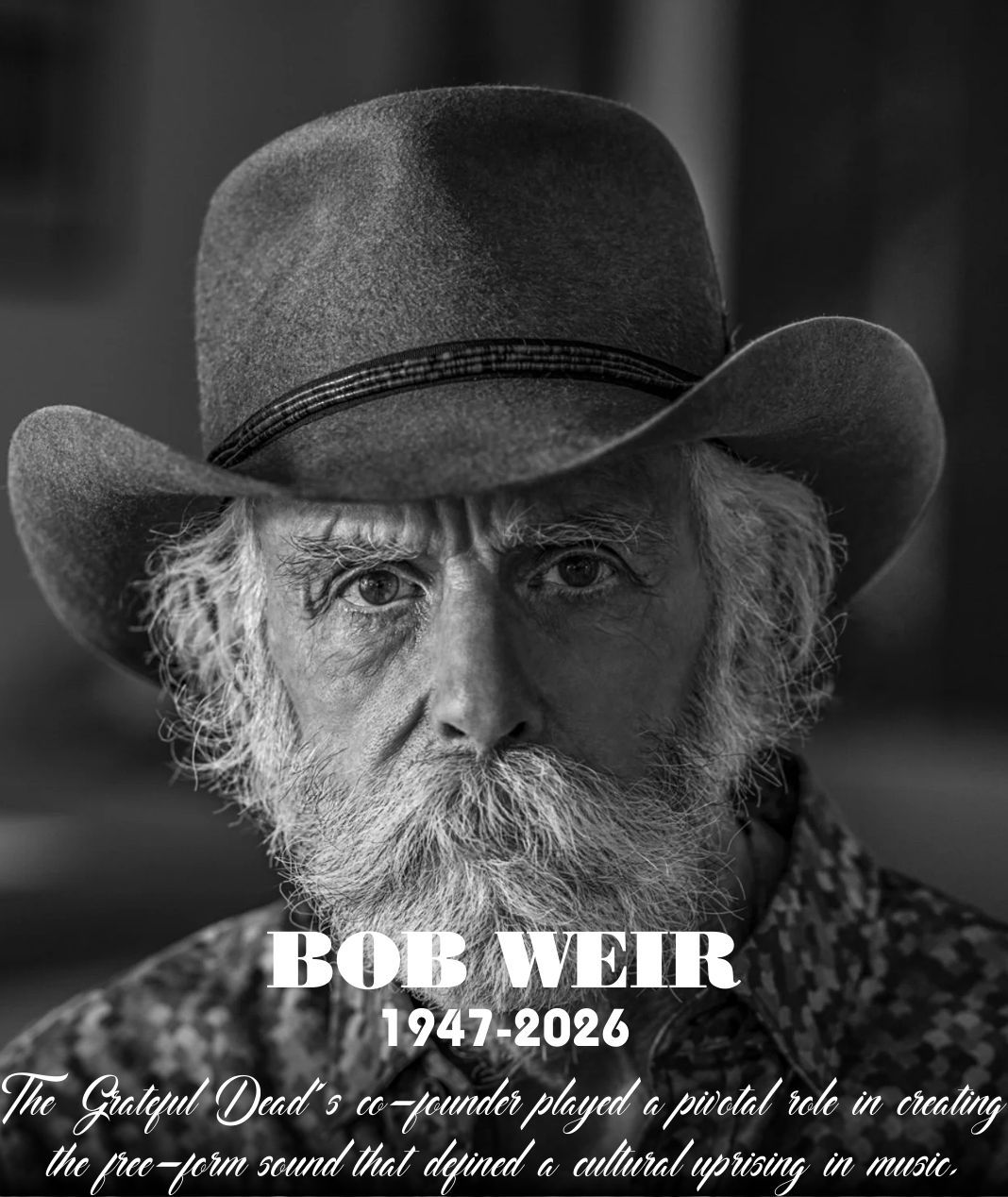

Bob Weir, a founding member of the Grateful Dead and one of the most quietly influential musicians in American history, has died at the age of 78. His passing marks the closing of a chapter that reshaped not only rock music, but the way generations understood freedom, community, and the power of shared experience. For millions, Bob Weir was never just a guitarist or a songwriter. He was a guide along a long, winding road where music was not consumed, but lived.

When the Grateful Dead emerged in the mid-1960s, America was restless, searching for meaning amid change and uncertainty. Weir, still a teenager at the time, stood at the center of a movement that refused to follow rules already written. The band rejected predictability, turning concerts into living conversations rather than rehearsed performances. No two nights were the same. No song was ever truly finished. And at the heart of that openness was Weir’s rhythm guitar — unconventional, fluid, and deeply human.

Unlike many rock figures of his era, Weir never chased dominance or spectacle. His strength lay in balance. He understood space, tension, and release, crafting rhythms that allowed the music to breathe. Songs such as “Sugar Magnolia,” “Cassidy,” “Playing in the Band,” and “One More Saturday Night” carried his unmistakable stamp — optimistic without being naive, joyful without ignoring life’s complexity. His voice, warm and unforced, sounded less like a declaration and more like an invitation.

The Grateful Dead became something far larger than a band. They became a culture. Fans followed them from city to city, forming a roaming community built on trust, memory, and the understanding that what happened inside those concerts could not be repeated or replaced. Weir embraced that bond with humility. He never treated the audience as spectators. They were participants, equal partners in a shared moment that existed only once and then lived on in memory.

After the death of Jerry Garcia in 1995, many believed the story had reached its natural end. But Bob Weir did not allow the music to be sealed in the past. Instead, he carried it forward with care and respect, leading new projects that honored the spirit of the Grateful Dead without attempting to imitate it. Through RatDog, Dead & Company, and later Wolf Bros, Weir demonstrated that legacy is not about preservation alone — it is about continuation with integrity.

In his later years, Weir’s performances took on a reflective quality. His movements were slower, his delivery more deliberate, but the connection remained powerful. Fans who attended those shows often spoke of a quiet understanding in the room — a sense that everyone present knew they were witnessing something precious, something finite. There was no rush to cheer. No need to shout. The music spoke clearly enough.

Beyond the stage, Weir was known as a thoughtful and principled individual. He spoke openly about the responsibility that comes with influence and the importance of community in an increasingly fragmented world. He believed music could still bring people together, not by overwhelming them, but by reminding them of shared humanity. In a time of constant noise, his approach felt almost radical in its calm.

Bob Weir leaves behind his family, his fellow musicians, and an immeasurable audience whose lives were shaped by the sound he helped create. His passing is not simply the loss of an artist, but the quiet closing of a doorway through which generations once stepped to feel less alone.

The road may now be silent, but the journey does not end. As long as a familiar chord drifts through the air, as long as listeners gather to share a song without knowing exactly where it will lead, Bob Weir’s spirit remains present — steady, generous, and forever part of the music that refused to stand still.